In a better world, the Israeli Peace Initiative, launched yesterday, would have been written not by a group of ex-generals and other public figures but by the Israeli government itself. In an even better world, Israel would have issued the proposal nine years ago, immediately after the Arab League ratified its own Arab Peace Initiative.

In a better world, the Israeli Peace Initiative, launched yesterday, would have been written not by a group of ex-generals and other public figures but by the Israeli government itself. In an even better world, Israel would have issued the proposal nine years ago, immediately after the Arab League ratified its own Arab Peace Initiative.If that better world had included a U.S. administration able to mediate muscularly in 2002, the narrow gaps between the two outlines for peace might have been quickly closed and an agreement signed. Back then, the number of Israeli settlers in the West Bank and Gaza -- not counting East Jerusalem -- was 216,000, compared with more than 300,000 today. The Palestinian Authority had not yet split into separate West Bank and Gaza governments. The barriers to implementing an accord were considerably lower. Many graves had yet to be dug for the Israelis and Palestinians who have since died at each others' hands.

Alas, we do not live in that alternative universe. In our world, the Israeli Peace Initiative was launched belatedly, in 2011. (The Hebrew text is here and an English translation here.) The signatories included Yuval Rabin, son of the assassinated prime minister and peacemaker, former military chief of staff Amnon Lipkin-Shahak, ex-Gen. Amram Mitzna, two former chiefs of the Shin Bet security agency, and an ex-head of the Mossad, along with onetime deputy foreign minister Yehudah Ben-Meir (a recovered rightist) and, most surprisingly, Adina Bar-Shalom -- daughter of Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, the spiritual leader of the ultra-Orthodox, hawkish Shas Party.

Utterly unsurprisingly, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's name does not appear on the list. The Israeli Peace Initiative can be read as a carefully compiled list of the diplomatic steps that Netanyahu desperately seeks to avoid: accepting the 2002 Arab plan as a framework for negotiation, using the pre-1967 borders as the basis for peace with the Palestinians and Syria, recognizing East Jerusalem as the Palestinian capital, and more.

Pessimists quickly argued that another peace proposal by out-of-power figures has virtually no chance of breaking the Israeli-Palestinian deadlock. But pessimism doesn't mean realism. It translates into something between inertia and unwarranted despair. The initiative could roil Israeli politics and feed a chain reaction leading to negotiations. But that depends on whether potential allies, domestic and international, overcome their own inertia and help the process.

The new initiative's first target is the Israeli political debate. It's meant to show that peace terms close to what Arab leaders have proposed are militarily safe and publicly legitimate. It also shows that Netanyahu is the obstacle, and that he must be replaced. Lipkin-Shahak, ex-Gen. and Mossad chief Danny Yatom, ex-Shin Bet chief Yaakov Perry, and other signatories speak the classic national-security language, very short on feelings, that has a strong influence in an anxious country. Their political allegiances, past or present, are not to the radical left, but to the center-left or center, precisely the part of the electorate that has seemingly lost interest in peace. Their endorsement for negotiating based on the June 4, 1967 borders -- that is, for leaving the West Bank and Golan Heights -- identifies that position as centrist and Netanyahu as the extremist.

The new Israeli proposal, I should stress, isn't a blanket endorsement of the 2002 Arab plan, also known as the Saudi Initiative, but a more detailed response. The text is more than twice as long as the Arab initiative. On the Jerusalem issue, it calls for leaving post-1967 Jewish neighborhoods in the east half of the city under Israeli rule. The holy site known to Jews as the Temple Mount and Muslims as Haram al-Sharif would be under Muslim administration but neither side's sovereignty. The pre-1967 borders would be adjusted on the basis of one-to-one land swaps. Unlike the Arab plan, the Israeli one makes explicit that there would be a passageway under Palestinian control connecting the West Bank and Gaza. The Arab plan calls for an "agreed" solution to the Palestinian refugee issue; the Israeli one says that refugees would be absorbed by the new Palestinian state with only a "symbolic" number entering Israel.

All of these details are products of the best moments in the sporadic Israeli-Palestinian negotiations since 2000. The gap between the unofficial Israeli proposal and the Arab initiative is real, but not large. A pessimist would say it remains unbridgeable, that a diplomatic rewrite of Zeno's paradox is at work: To get to peace, each side must first traverse half the distance to a compromise. Then it must traverse half the remaining distance, and then half of what is left, and therefore it is impossible ever to arrive. Motion itself is an illusion. Real life, however, has never cared about Zeno's sophistry. It is possible to move and possible to arrive.

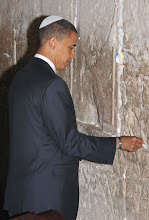

For that to happen, some warm responses to the Israeli Peace Initiative would help. Tzipi Livni, head of the parliamentary opposition, should endorse it, showing that her Kadima Party really is centrist, security-oriented, and an alternative to Netanyahu. Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas should quickly describe the Arab and Israeli initiatives as precisely the framework needed for negotiations. Endorsements by prominent American Jews -- following the lead set by the pro-peace lobby J Street and Americans for Peace Now -- would make it easier for members of Congress to laud the plan. That, in turn, would create the right atmosphere for President Barack Obama to lay out his own proposal for an agreement, citing the unofficial Israeli proposal as a foundation.

In a recent article, veteran American peace negotiator Aaron David Miller both encouraged Obama to take bold steps on the Israeli-Palestinian front and expressed doubt that the president would risk doing so until after he is re-elected. Ostensibly, waiting is the cautious path. Second-term presidents are stronger and less constrained.

But a world in which Israeli-Palestinian peace is put off until 2013 is likely to be even uglier than the one we live in now. The real gamble would be to delay; the cautious path is to act immediately. That's why the Israeli Peace Initiative, belated as it may be, is still too good an opening to ignore. Gershom Gorenberg is a senior correspondent for The Prospect. He is the author of The Accidental Empire: Israel and the Birth of the Settlements, 1967-1977 and The End of Days: Fundamentalism and the Struggle for the Temple Mount. He blogs at South Jerusalem.